#3 - Pandemic: state capacity, federalism, and the future

Early on in the coronavirus outbreak, a Washington State epidemiologist who was running a research program on early flu detection was able to develop a test to screen for COVID-19. She wanted to begin using the new test to track what her and her team suspected was community transmission from Washington State’s “patient zero,” the first confirmed case of COVID-19 in the country.

The problem was that she wasn’t allowed to use it.

A March 10th piece in the NY Times explains why:

…Dr. Lindquist, the state epidemiologist in Washington, wrote an email to Dr. Alicia Fry, the chief of the C.D.C.’s epidemiology and prevention branch, requesting the study be used to test for the coronavirus.

C.D.C. officials repeatedly said it would not be possible. “If you want to use your test as a screening tool, you would have to check with F.D.A.,” Gayle Langley, an officer at the C.D.C.’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Disease, wrote back in an email on Feb. 16. But the F.D.A. could not offer the approval because the lab was not certified as a clinical laboratory under regulations established by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, a process that could take months.

Lindquist and her colleague Dr. Helen Y. Chu, a Seattle infectious disease expert, were stuck for weeks trying to wade through the federal bureaucracy to get permission to use a test they could already perform on their own. And what they found were roadblock after roadblock.

Meanwhile, other labs across the country were facing similar problems:

Private and university clinical laboratories, which typically have the latitude to develop their own tests, were frustrated about the speed of the F.D.A. as they prepared applications for emergency approvals from the agency for their coronavirus tests.

Finally, Lindquist and Chu decided to go rogue: they started testing the samples they had without permission from the CDC or the FDA. On day one of testing, they got a positive. And so, in violation of federal rules against communicating the results or using them for clinical purposes, they notified state health officials, who then set in motion processes for communicating with Washington State residents who tested positive and taking appropriate containment measures.

As the host of the NY Times podcast companion piece, Michael Barbaro observed that, on the one hand it’s good that Chu and her team went rogue. And on the other hand, it’s extremely worrying that a team of doctors had to go rogue in order to help combat a public health crisis.

State capacity libertarianism

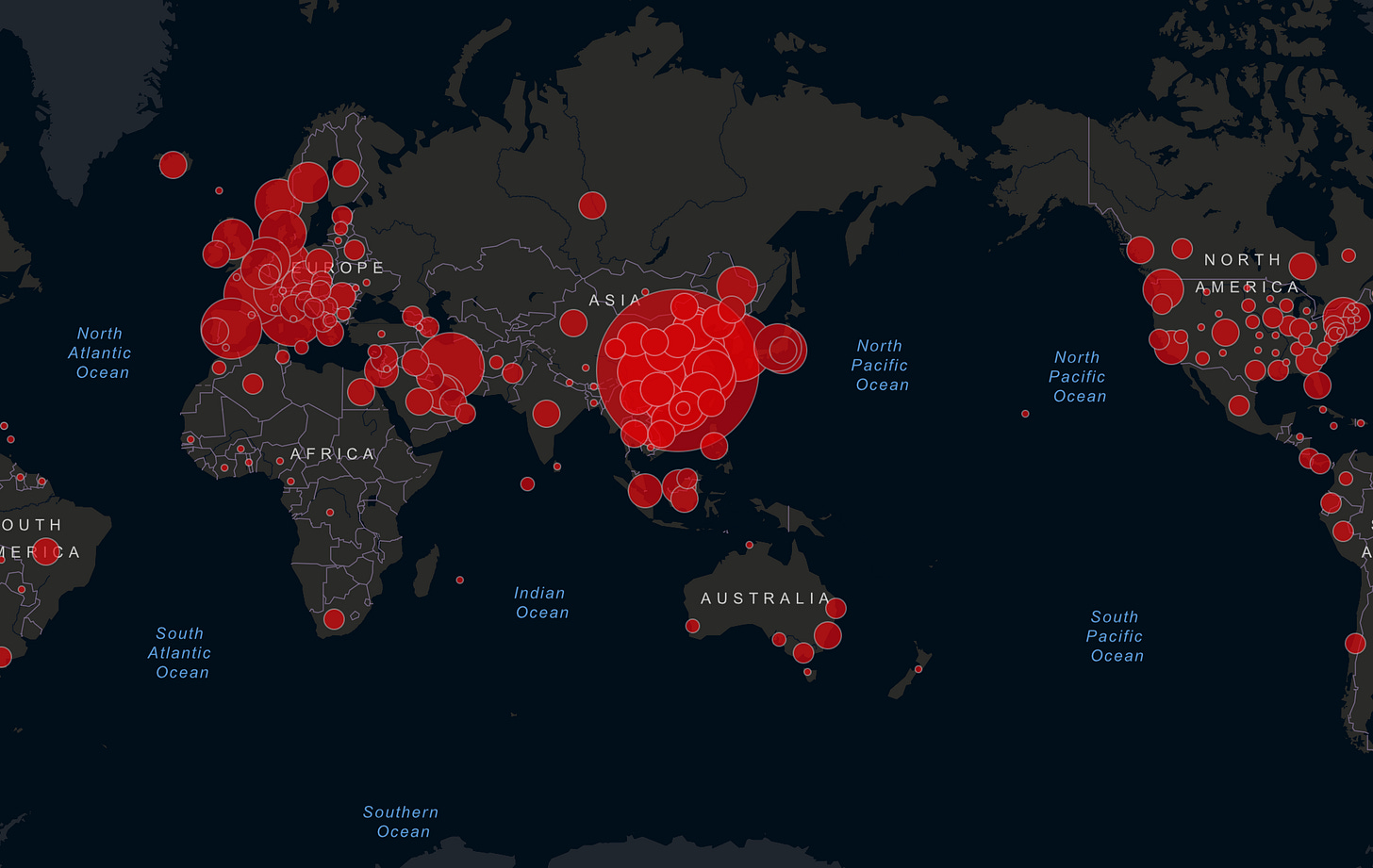

That episode and the much wider, continued failure of the United States to ramp up a rigorous testing program to help contain the spread of COVID-19, has opened a debate about state capacity, federalism, and the limits of our democracy. Indeed, the current pandemic is testing the very notion that liberal democracies are capable of adequately responding to a pandemic on this scale.

While China has leaned on its autocracy, placing hundreds of millions of people under lockdown, and leveraging the full force of the state toward a national program of screening, testing, isolation, and treatment, the United States and countries in Western Europe have largely dragged their feet. They want the bars to stay open, for people to keep on with their lives and their vacations, and, in the case of president Trump, for the stock market to resume its inexorable upward march, so that he can win re-election.

The idea of “state capacity libertarianism” was coined by economist Tyler Cowen in a post this past New Year’s which now seems incredibly prescient. Cowen argued that libertarians should essentially want the state to have the capacity to capably manage a handful of important functions, such as building and maintaining national infrastructure, subsidizing science, and maintaining ad promoting good quality governance in the realm of, say, free and fair elections.

One could presumably add to that list the ability to coordinate an effective response to a global pandemic. For if there is one thing COVID-19 has revealed in no uncertain terms, it’s that the difference between a competent government response to a pandemic (South Korea, Singapore) and an incompetent response (United States) is consequential indeed.

Here is Eli Dourado, of the Center for Growth and Opportunity:

Dourado is right. The U.S. needs to combine its talent for private sector entrepreneurialism and industry with competent state capacity that doesn’t get in the way with dumb bureaucracy.

Slow to respond

As Cowen himself wrote in a recent Bloomberg column:

It is no accident that America is so often so slow out of the starting gate. The federal government is large and complex, and the American people do not always elect the most intellectual or science-minded of leaders. Federalism means American politics has many moving parts, and the government tends to work closely with the private sector, heightening coordination problems and slowing response times. For all America’s reputation as the land of laissez-faire, it is in fact highly bureaucratized, with the health-care sector an especially bad offender.

And yet:

As time passes, the number of discrete decision points in the U.S. system goes from being a drawback to a strength. For instance, it turns out that the University of Washington had been developing an effective testing kit several months ago, for fear that Covid-19 would spread widely. Washington State is now in the testing lead, and virologists there are working very hard to collect and interpret data, setting an example for others. Commercial companies such as Quest Diagnostics and LabCorp are now developing tests as well, with further interest likely to follow. American institutions are some of the most productive and flexible in the world, at least once they are allowed to operate.

That “being allowed to operate” part is crucial. According to a March 10th Politico report, not only are we facing a shortage of tests themselves, but we are facing a shortage of RNA extraction kits needed to perform the tests, and one of the big reasons for that is that the FDA has apparently only approved one private company to make the kits.

As Noah Smith, another Bloomberg writer, observed:

Clearly, part of the problem with the U.S. response to COVID-19 is indeed too much regulation. It’s not hard to imagine what the Mitch McConnells and the Mitt Romneys of the world would say if there were a Democratic president in charge - they would be riding victory laps with their ideology firmly in tow.

But instead the GOP Congress is beholden to a science-averse egomaniac who captured the GOP in a hostile takeover and whose electoral fortunes now mirror their own. But if this weren’t the case, small government conservatives would be having a field day with these “government got in the way” stories.

Again, there is a gaping ideological space that the GOP has abandoned.

But the facts remain, and Democrats shouldn’t be afraid to say it: we need more flexible, more nimble government, with less regulation and more capacity for innovation. So that a group of doctors in Washington don’t have to go rogue just to do their jobs in the middle of a public health crisis.